Disclaimer: This post aims to shed light on the distinctions between eating disorders and disordered eating, drawing from my experience and expertise as a dietitian. However, it’s crucial to understand that the content provided here is for informational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Eating disorders are complex issues with significant physical and psychological implications. If you or someone you know is struggling with these issues, seek guidance from qualified healthcare professionals or specialized organizations. Remember, help is available, and you are not alone!

There is a fine line between an eating disorder and disordered eating. As a dietitian specializing in this field, I work with clients across the entire spectrum. I have noticed that the biggest differentiating factors are the frequency and severity of behaviors as well as how they affect the individual’s overall life and mental state. Before diving into eating disorder vs disordered eating, let me first break down what an eating disorder is.

Table of Contents

What is an eating disorder?

Generally speaking, an eating disorder (ED) is a biologically based mental health disorder that affects an individual’s thoughts and behavior around food and body. The following are common EDs that I see in my practice (though not an exhaustive list). These conditions are defined in and diagnosed based on the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V).

NOTE: As a dietitian I cannot diagnose individuals with EDs, but I am skilled at identifying thoughts/behaviors, referring out to the appropriate clinician, and supporting recovery.

Overview of eating disorders

Eating disorders are diagnosed based on the presentation of behaviors and possibly one’s relative body weight.

Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most common eating disorder and widely under-diagnosed. Given this, I’m going to start here!

Binge Eating disorder

BED is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating, defined as meeting the following criteria:

- Eating, within a 2-hour period, an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most would eat in a similar time frame/situation

- A sense of lack of control over eating

and

the episodes are associated with 3 or more of the following:

- Eating much more rapidly than normal

- Eating until uncomfortably full

- Eating large amounts of food when not physically hungry

- Eating alone, often due to shame around how much food is eaten

- Feeling guilty, depressed or disgusted with oneself afterward

With BED, there is no attempt to compensate for these behaviors like there are in bulimia nervosa.

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is characterized by binge eating followed by inappropriate behaviors to compensate for the binge. For example, self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics or other medications, fasting, or overexercising.

Those with BN also present with over preoccupation with their body weight/shape.

Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is characterized by the restriction of food intake leading to a significantly low body weight RELATIVE to age, sex, development, and physical health. Relative is the key word here – body weight without any context of growth history really doesn’t provide any valuable information.

For example, if a teenager has always been on the higher end of the growth chart (e.g. 95th percentile for weight) and they suddenly drop to the 60th percentile for weight, they are contextually underweight despite being relatively “average” compared to their peers.

In the example, the teen technically didn’t lose much weight, and in fact some years gained weight, but clearly fell off the chart. They started at the 90-95th percentile at 3 years old, maintained until adolescence, and by age 17 had fallen to the 50-60th percentile. As a dietitian, this is a huge red flag for me! This video goes into more detail.

Those with AN also present with an intense fear of weight gain and resist any attempt to restore weight despite the seriousness of the disorder. They also present with body dysmorphia, or a distorted perception of their physical appearance.

While these three are the most common EDs, some individuals do experience significant distress around eating and body but don’t necessarily fall into one of these “buckets”. There are a couple of other EDs that they may fit.

Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED)

OSFED is kind of like a “catch-all” bucket for anyone that may have eating challenges that don’t fit into the criteria for one of the above established definitions. Despite the ambiguous diagnosis, these individuals are not at any lower risk for physical or mental impairments.

Examples of OSFED include:

- Atypical anorexia, or someone who has all the symptoms of anorexia except for weight loss (honestly, more “typical” than what I’ve described above!)

- Infrequent binge/purge episodes (therefore not meeting the diagnostic criteria for BN, though still a significant health risk)

- Infrequent binge eating episodes

- Purging disorder

- Night eating syndrome

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)

ARFID is a relatively new addition to the DSM, and I am seeing more and more clients with ARFID recently.

ARFID is a little different from the other EDs in the sense that there is no over-preoccupation with weight/shape.

Instead, there is a persistent failure to meet nutritional needs associated with at least one of the following:

- Significant weight loss OR not achieving expected weight gain (e.g. falling off the growth chart that they were previously right on track with)

- Significant nutritional deficiency

- Dependence of tube feeding or nutrition supplements (like Boost or Ensure)

- Significant interference with day-to-day life (e.g. unable to eat outside of the house due to food preferences)

ARFID has a few subtypes that drive the ED, including sensory avoidance, lack of interest in food, or the fear of adverse events like choking.

Prevalence of EDs and impact on physical and mental health

Eating disorders affect at least 9% of the population worldwide, including 29 million Americans. You cannot “see” an eating disorder or make assumptions on diagnosis based on body weight or size. EDs are not just a “phase” that affect thin, white, well-off women.

EDs have severe and fatal consequences – they are the 2nd highest mortality rate among psychiatric illnesses. Impacts on physical health include gastrointestinal damage, esophageal tears and rupture, fatal blood sugar fluctuations, cardiovascular injury or death, hormonal disruptions, and bone damage. Psychological impacts include depression, anxiety, and suicide.

Eating disorders are not a choice. The solution to “just eat” may seem rational and reasonable to someone without an ED, but what they can’t see is the stress, anxiety, and overwhelming guilt and shame that overtakes the person suffering.

What is Disordered Eating?

All eating disorders are characterized by disordered eating, but not everyone who practices disordered eating has or will develop an eating disorder. So where is the line?

Reality is, the line is nuanced. That’s because in many cases, an ED is diagnosed based on the extent that the behaviors affect an individual’s life.

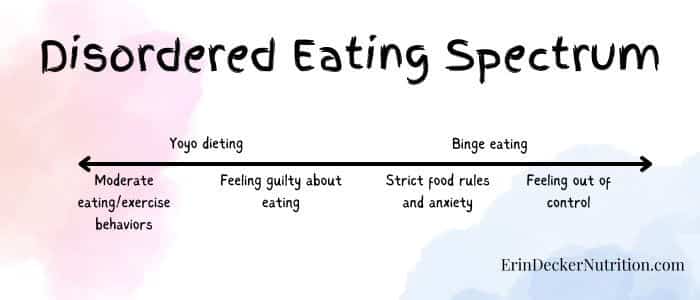

I like to think of disordered eating and eating disorders as a spectrum. Each individual’s experience will vary based on their own values and priorities.

Unpacking the spectrum of disordered eating

I like to describe the spectrum of disordered eating as a range from general dieting, to increasingly rigid behaviors, to an eating disorder.

Some people may be able to “eat healthier” and exercise more and improve their health. Others can’t help but fall into extremes and damage their mental and physical wellbeing in the process. If this describes your experience, please know that it is not your fault. EDs are complex disorders that are brain- and biology-based. Once you are in the cycle, it’s common to feel out of control and helpless.

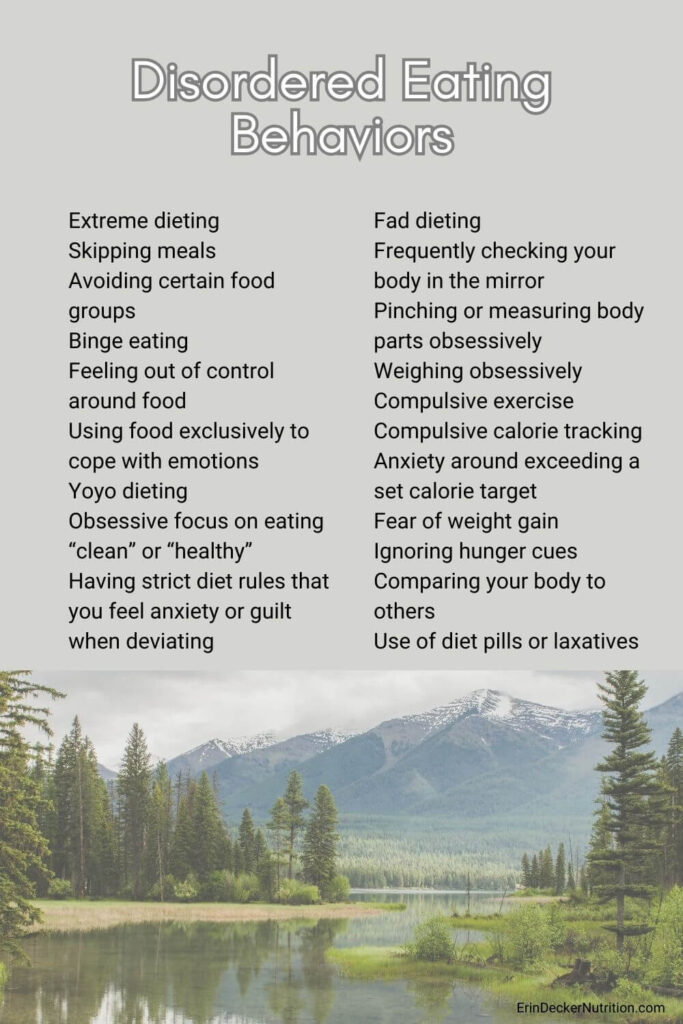

Examples of disordered eating behaviors

I’ll list some common behaviors below, but keep in mind anything can be disordered if it causes mental or emotional distress to you.

- Extreme dieting

- Skipping meals

- Avoiding certain food groups

- Binge eating

- Feeling out of control around food

- Using food exclusively to cope with emotions

- Yoyo dieting

- Fad dieting

- Obsessive focus on eating “clean” or “healthy”

- Having strict diet rules that you feel anxiety or guilt when deviating

- Frequently checking your body in the mirror

- Pinching or measuring body parts obsessively

- Weighing obsessively

- Compulsive exercise

- Compulsive calorie tracking

- Anxiety around exceeding a set calorie target

- Fear of weight gain

- Ignoring hunger cues

- Comparing your body to others

- Use of diet pills or laxatives

This is not an all-inclusive list, and also keep in mind these aren’t all inherently disordered. It is worth discussing with a medical provider who is well-versed in eating disorders to determine how the behaviors are affecting you.

Causes and Triggers of Disordered Eating

I know it can feel confusing to see these behaviors written out above, especially when many of these are “praised” in our culture as being a positive thing to do for your health. For example, exercising to burn off your dessert, eating “healthy”, or tracking calories are often encouraged by wellness and medical professionals.

That being said, dieting is one of the strongest predictors of developing an eating disorder. So why do we do it?

Of course, there are health reasons someone might go on a diet. Much of our medical community emphasizes the importance of a healthy lifestyle to prevent chronic disease.

There are also societal pressures and beauty standards that affect our desire to look a certain way. Studies show that eating disorder onset is highest during adolescence in westernized societies which value the thin ideal.

And lastly, there are psychological and emotional triggers for eating a certain way. Someone might eat (or restrict) as a means of coping with difficult emotions or to deal with trauma.

No one can say exactly what causes an eating disorder, or what makes one person more susceptible than another.

Recognizing the Differences

Key Difference Between Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating

The key differences between EDs and disordered eating include the frequency and severity of behaviors as well as the impact on health and daily life. The DSM-V helps provide some objective criteria here, and beyond that, it is worth consulting a mental health or nutrition professional to unpack how your eating is affecting your life.

Importance of Early Intervention

Early intervention is key to full recovery from an eating disorder. Whether your eating constitutes a full-blown ED or not, it is ok and NECESSARY to ask for support if it is something that is disrupting your life.

I realize getting treatment is a privilege. It can be costly and access is a problem. Many providers near me have wait lists that are months-long. That being said, a common theme in EDs is that the sufferer is not sick enough to justify treatment.

Don’t let your ED voice be the judge of your worthiness for treatment!

Recognize the warning signs

The following are warning signs that your eating behaviors are at risk for an ED (or someone you know):

Rapid weight fluctuations

Mood swings

Difficulty regulating body temperature

Preoccupation with food, weight and/or appearance

Worsening gastrointestinal health

Interrupted pubertal development

Loss of or irregular menstrual cycle

Low libido

Dizziness

Fainting

Using the bathroom soon after eating

Scares or calluses on the back of hand

GERD or esophageal sores

Dental erosion or cavities

Low productivity

Hemorrhoids

Edema/swelling

Hiding or hoarding food

Poor concentration

Baggy, tight, or inappropriate clothes

Stress fractures

Poor wound healing

Heart palpitations

Bradycardia

Low blood pressure

Irritability

Fatigue

Insomnia

Excessive fluid intake

Fine hair over the body

Hair thinning or loss

Dry skin/brittle nails

Poor self esteem

Abdominal bloating

Low blood sugar

Getting full quickly

Nausea

Heartburn

Constipation or diarrhea

Suicidal thoughts

Withdrawal from usual activities or in general

Eating alone

Feeling depressed or ashamed after eating

Hallucinations – visual or auditory

Rigid or excessive exercise patterns

OCD-like rituals around meals and movement

Commenting on body size

Anxiety or panic attacks

Depression

How to recover from an Eating Disorder

Recovering from an eating disorder takes time, patience, commitment, and a massive amount of bravery and self-compassion. It involves healing your body and your mind.

Nutrition and medical support is essential because our body’s nutrient stores are depleted. This is the truth regardless of body size! Nutritional rehabilitation involves nourishing your body with an adequate amount of food, at regular intervals throughout the day, and gradually building in variety and spontaneity.

This process requires medical monitoring because refeeding your body can result in uncomfortable to dangerous side effects. Refeeding syndrome is a deadly electrolyte shift that can happen when food volume shifts from minimal to adequate. Bloating and early satiety are common in the early stages, followed by extreme hunger. Bowel changes like diarrhea and constipation are also likely. Despite these challenges, weight restoration and refeeding are necessary – without adequate nutrition, your brain will not recover.

Mental health support is the final key: as your body rehabilitates, your mind will start to recover. This allows you to do the difficult mental health work with a licensed therapist or counselor.

While we know that full recovery requires nutrition, medical, and mental health treatment, I’ve also found that there is no “right” way to recover. Recovery is not a straight line and lapses and relapses are likely.

Embrace “Normal” Eating

After you’ve done the work to heal your body physically and are on your path toward recovery, you can work toward “normal” eating.

What the heck does that even mean??

“Normal” is a vague term that means different things depending on your own food culture. I like to think of “normal” eating as being “recovered eating”. This may include:

- Exploring a balanced and intuitive approach to food

- Listening to hunger and fullness cues

- Enjoying a variety of foods without guilt

- Eating for nourishment and pleasure

- Practicing self compassion and acceptance

- Fostering a positive mindset toward eating

- Critiquing societal norms and beauty standards

- Embracing body diversity

In Conclusion

Disordered eating exists on a spectrum. There is often a fine line between an eating disorder and disordered eating. All eating disorders consist of disordered eating behaviors, but not all behaviors reflect an active eating disorder.

That being said, disordered eating behaviors are a slippery slow toward the development of an ED, and dieting is the #1 risk factor for the development of an ED. Get to know the warning signs, consider whether you are a “normal” or “recovered” eater, and don’t be afraid to reach out and consult a professional.