Table of Contents

Is your body weight out of your control? The set point theory suggests so!

Most diets fail. I’ve heard estimates of up to 95%. Some may argue that it’s not the diet per se, but how were approaching it. For example:

- Fad diets are unsustainable

- Diets encourage all-or-nothing thinking

- Dieters have unrealistic expectations

- Ultra-processed foods are addicting

And for what it’s worth, I do agree with these points. Even before fully embracing the anti-diet space I preached the importance of sustainability, realistic expectations, and challenging negative thoughts.

But if you do everything “right” – that is, you make gradual, sustainable lifestyle changes, set realistic goals for yourself, and eat mostly whole foods – will your diet actually work?

The set point theory suggests not. But what is the evidence for the set point theory?

What is the set point theory?

The set point theory hypothesizes that your body is genetically predisposed to a set weight range. It will resist any attempt to change it through biological mechanisms.

For example, when you eat a higher calorie meal, your body increases its calorie burn to compensate. When you burn more calories through exercise, your body increases hunger.

This means that dieting, even if it is “sustainable”, will ultimately result in a return to your pre-diet weight.

What does the research say about the set point theory?

The set point theory is actually one of a collection of theories, all with different explanations for why body weight is hard to manipulate.

It’s important to recognize that these theories are just that – theories. They haven’t been proven.

That being said, there is substantial evidence that something is defending body weight.

Speakman and colleagues describe the set point theory as an active feedback mechanism driven by physiologic, genetic, and molecular biology. This means that it is entirely out of our conscious control.

The feedback mechanism identified is based in part on hunger hormone regulation, first identified by researcher G.C. Kennedy in the 1950’s.

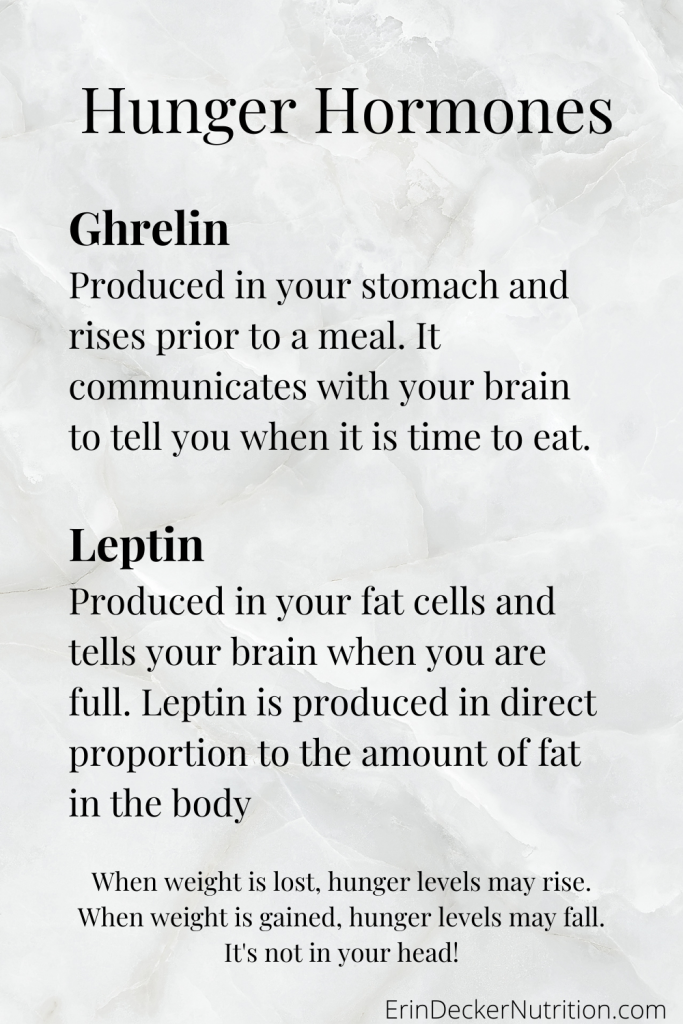

Hunger Hormones: Ghrelin and Leptin

Your hunger and fullness hormones are ghrelin and leptin, respectively. They work on a negative feedback loop to control food intake.

Ghrelin is produced in your stomach and rises before a meal. It communicates with your brain to tell you when it is time to eat.

Leptin is produced in your fat cells and tells your brain when you are full. This hormone is produced proportionately to the amount of fat in the body (the more body fat, the more leptin being produced).

When fat is lost, leptin levels fall and ghrelin levels rise. This means you feel hungrier during periods of weight loss and restriction (see? it’s not in your head!)

In theory this would also be the case during periods of weight (or fat) gain. However, studies do not seem to support this as strongly as they do for weight loss. This might explain why it is (for most people) easier to gain weight than it is to lose weight.

Physiological Adaptations Regulate Weight

In addition, the body adapts to a higher or lower calorie intake by burning more or fewer calories, respectively.

The body responds to calorie restriction by reducing metabolic rate and turning off non-essential functions. This is commonly referred to as “starvation mode”.

We also see a slowed digestive tract, disrupted menstrual cycles in women, difficulty concentrating, and slowed heart rate. By shutting down these functions, the body is able to conserve energy (i.e. calories) while maintaining the same weight.

This is further supported from the research done on The Biggest Loser contestants. Despite being at a significantly lower weight than they started at, they are burning far fewer calories than would be expected when compared to someone of a similar height and weight without the dieting background.

Limitations of the Set Point Theory

The set point theory explains a lot when it comes to weight management: it’s difficult and often out of our control. However, it doesn’t explain the whole picture.

We know from observational surveys that population-wide body size has increased over time. In addition, social and environmental factors, such as going off to college or getting marred, affect weight.

If the set point theory were completely true, we wouldn’t see this trend. Our bodies would defend their “set point” even during these periods of transition.

Researchers have proposed alternative theories to account for these limitations.

Alternative Theories to the Set Point Theory

Speakman and colleagues described three alternatives to the set point theory to explain some of these limitations.

Settling Point Theory

The settling point theory acknowledges the impact that social and environmental factors have on body weight.

This theory highlights that our metabolism (how many calories we burn) is related to how much mass our body holds. As we eat less, mass is lost, and calorie burning capacity goes down. If we are in an environment that encourages a higher calorie intake, we will ultimately put mass back on due to our previously slowed metabolism.

This theory supports the more traditional weight loss theory of “calories in = calories out”.

However, weight science isn’t as simple as that.

The next two models attempt to combine both aspects of the set point and settling points.

General Intake Model

This model suggests that body weight is impacted by a variety of physiological, environmental, psychological, and dietary factors. Some of these are within our control and some are not.

Compensated factors are those that are biologically ingrained and out of our control. These include the factors explained above:

- the leptin/ghrelin feedback loop involved in hunger and fullness regulation

- the metabolic adaptations that take place during calorie restriction

These affect food intake AND are affected by food intake. For example, you are hungry, you eat, you get full, then you stop eating.

Uncompensated factors include the following factors:

- environmental

- social

- cultural

- psychological factors such as emotional/stress eating and other reasons we may eat beyond our hunger cues.

These factors influence how much and what we eat, but they are not affected by how much we have already eaten. For example, we may continue to eat when stressed even though we are physically full.

This model is a combination of set point and settling point. It proposes that we can experience these interactions at the same time. The impact on weight depends on individual variation and genetics.

Dual Intervention Model

The dual intervention model switches things up even further: it hypothesizes that we don’t just have one set point weight, but rather a range of weights with upper and lower boundaries.

Within those upper and lower boundaries we are free to manipulate weight as we see fit. Once we go outside of them our body will start to regulate with the adaptations described in the set point theory. This could explain why it is easy to manipulate weight within a small range (e.g. 5-10% body weight) but going beyond that is more difficult.

This model is the only one with evolutionary explanation. In theory, this allowed for humans to maintain a lower threshold to prevent starvation, and an upper threshold to reduce the risk of predation.

This also adds to the explanation why some people have difficulty gaining weight. Historically, it was not advantageous to be at a higher body weight since it would be a higher risk for predation. But these days? That is less of a risk. So, that defense has been evolutionarily phased out, so to speak. Some people may still carry that genetic predisposition though.

Additional Considerations

Clearly, weight science is complex! There are other factors to consider as well.

Psychological Factors: Reward Deficiency

Eating is pleasurable and provides our brain with a reward. This is a good thing, because eating is essential to survival.

However, there are instances when the reward we get from eating is reduced and yet we are still chasing that same “rewarding” feeling. Meaning, we continue to eat beyond fullness because we are not satisfied. Some might liken this to “food addiction”.

But whether you can be addicted to food is up for debate. You experience “reward deficiency” when you do not factor food preferences into your eating decisions. Restriction reduces reward.

Researchers have found that this reward returns when we allow ourselves to eat what we want.

Sound familiar?

This is a major element of intuitive eating. Intuitive eating encourages you to make peace with food, discover satisfaction, and honor your hunger which leads to fewer instances of binging and obsessive thoughts about food.

How to calculate your set point weight

Regardless of what theory you choose to buy into, there is undoubtedly some type of regulation around body weight. Losing weight (and for some, gaining weight) is hard.

There is no way to calculate or predict your “set point weight”. Based on the research we have, we can estimate what is called a biologically appropriate weight based on family history and growth charts.

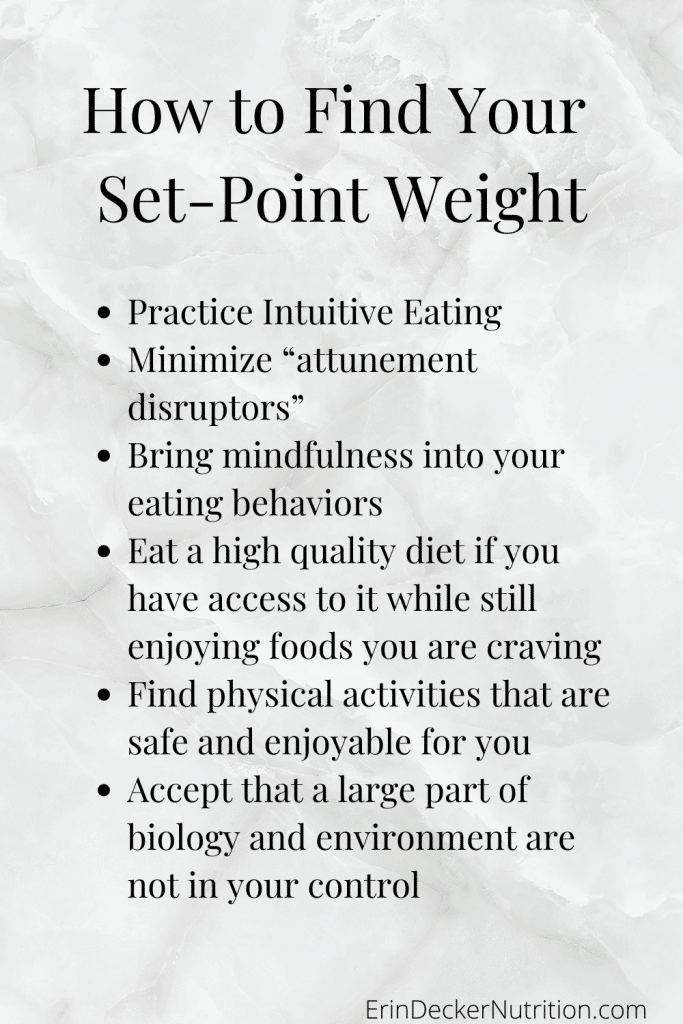

In my experience, following a pattern of intuitive eating can help you reach your set point weight. This means one can:

- tune into hunger and fullness cues, which are regulated by ghrelin and leptin

- minimize “attunement disruptors”, i.e. any life stress that makes tuning into your needs more difficult, such as lack of sleep and high stress

- bring mindfulness into your eating behaviors

- eat a high quality diet if you have access to it while still enjoying foods you are craving to minimize “reward deficiency”

- find physical activities that are safe and enjoyable for you

- accept that a large part of biology and environment are not in your control

Can you change your set point weight range?

There is some evidence that weight loss surgery and dieting itself seem to influence the body’s set point.

Weight Loss Surgery May Lower Set Point

A review of the evidence suggests that weight loss surgery, specifically gastric bypass surgery, can “reprogram” the set point.

Those who have received weight loss surgery often sit at a lower body weight, even following some weight regain from their lowest point.

This could be related to any or a combination of factors, including changes in hunger/fullness hormones, changes in the gut microbiome, and changes in neural communication pathways. Rodent and human studies have not been able to pinpoint any single factor responsible for this observation, however.

Dieting May Increase Set Point

Studies have shown that restriction followed by “ad libitum” refeeding (eating as desired rather than prescribed) results in weight gain beyond the initial starting point.

This is evident in the classic Minnesota Starvation Experiment. In this study, healthy volunteers followed very low calorie diets to better understand the impact of starvation during World War II. Further analysis has shown that these participants experienced weight regain beyond their initial starting point, upwards of 145%.

Dulloo and colleagues refer to this as the “overshoot theory”. The body has safeguards in place to increase fat mass following periods of depletion.

Anyone who has a long history of dieting may also be familiar with this experience: you lose weight, then regain even more than you lost.

However, researchers have found that this rebound weight regain tends to settle within 5% of the initial weight within a year or so.

So does it permanently change your “set point”? I don’t think we have an answer. I suppose it can feel like it if you are trying diet after diet, which could certainly be tempting when you experience that “overshoot”.

If you are unhappy with your weight, chances are calorie restriction is not the answer for you (at least, not beyond a few pounds.) It is unlikely to result in sustainable weight loss due to biological changes that take place, as well as psychological changes that make living with it very emotionally draining.

Accepting your set point weight

Your theoretical set point weight is one that you can maintain with minimal effort. It allows you to follow a pattern of intuitive eating: honoring hunger, challenging dieting messages, and listening to your body. If you believe you are engaging in these behaviors, there is a good chance you are at your set point weight.

But what if it is not the weight you expected? See below for some tips to help you accept your set-point weight.

Accept that bodies change over time

Our bodies are not supposed to look the same as they did at age 16, 20, 50, etc.They are constantly changing. Very few people weigh what they did when they graduated high school or college and that is normal and expected.

Focus on the benefits

Focus on what you gain by accepting your weight. For instance: no longer obsessing about food, breaking the binge-restrict cycle, or being able to eat all foods without guilt and anxiety.

Work on your body image

For many people, poor body image is the driving force behind dieting. Body image is also about perception. Remember that our perception can change!

Recognize that health is more than your weight

If you are pursuing weight loss for the sake of your health, remember that intuitive eating demonstrates improvements in health without the negative consequences of traditional dieting.

Additionally, many factors beyond diet influence our health. If focusing on dieting and weight loss is negatively impacting your emotional and mental wellbeing, it may not be worth it.

Find support

Take inventory of the people and messages around you. See if you can modify your social media feeds to show messages that are supportive of an anti-diet approach and incorporate bodies of all shapes and sizes.

Accept that it can take time

Most people have “good days” and “bad days” when it comes to body image. We also know rationally that our bodies do not change much from one day to the next. If this is true for you, see if you can identify some patterns in those good and bad days.

For instance: do the bad days follow stressful situations? Or specific experiences? If so, you can know for sure that it doesn’t actually have anything to do with your body.

Bottom Line

Is there much evidence for the set point theory? I’d say so!

While there are a lot of unanswered questions about the set point theory, it is clear that there is a powerful mechanism in place that makes sustainable weight loss difficult.

Messages such as “lose weight” can be harmful because they do not consider all of the nuances involved in weight science. It’s an easy message that in theory might improve someone’s health, but in practice may do more harm than good when you factor in the psychological effects of restriction and physical impacts of weight loss and regain (i.e. weight cycling).

Body acceptance and following a pattern of intuitive eating can help you attain all of the benefits of a healthy lifestyle without the risks of restriction and dieting.

Want to get started with intuitive eating? Download my free tips below!

When one’s body weight doesn’t seem to be consistent, it’s definitely worth considering the set point theory, as you put into great detail here. Very nice!

There is definitively truth in the set point theory.

In fact, based on my own experiences, I would propose the set pointS theory.

My weight increased in several phases during my lifetime, starting from ideal 90 kg all the way to 120+.

The phases which lasted for years were at 90, 95, 101-103, 107-108, 112-114 & 118-120 kg. During those periods, no matter how much more or less I ate the body maintained the limits. However when a prolonged diet took place, the body broke the current set point and settled to the next one, up or down (down when fasting).

How long is needed to “jump” into the next level? I would say two to three weeks for gaining and at least six weeks for loosing.